The Pyramid of Reading Comprehension

Something I often encounter among young people is underdeveloped reading comprehension. That is, the ability to truly understand and internalize what a text is saying. Poor reading comprehension can be difficult to discern, as children who struggle with it may still sound fine when they read aloud. They sound out the words with ease, they know what the words mean, and they can move across the page quickly, yet they do not “get” what they are reading. This can be frustrating for parents and tutors; it can even provoke impatience. (“I know you know what you’re reading. What do you mean you don’t get it!?”)

In this article, we will discuss the mechanics of reading comprehension and how it rests on several other reading skills.

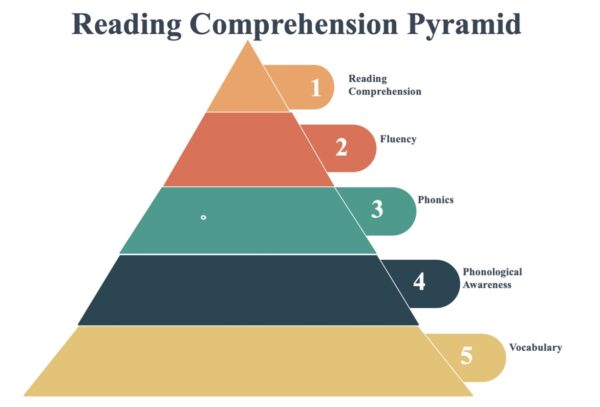

The Reading Comprehension Pyramid

The first step towards building sound reading comprehension skills is recognizing that reading comprehension does not emerge in a vacuum. We often assume that phonics and vocabulary are enough to create a strong reader—that once a child can sound words out and learn what those words mean, he is on his way to becoming an accomplished reader. In other words, there is a tendency to entirely equate phonics and vocabulary with reading, when in reality, they are merely components of it. Let’s learn a bit about the structure of reading comprehension to see why this is the case.

Reading comprehension is a complex skill that comprises several other skills. It is, in a sense, the culmination of several other skills upon which it depends and which it emerges out of. This is best illustrated by the Reading Comprehension Pyramid, which shows the hierarchy of these abilities and how they feed into reading comprehension:

The pyramid demonstrates how reading comprehension is a complex process built upon other foundational skills. If these foundational skills are underdeveloped, it becomes difficult for a child to develop reading comprehension. Let’s look at each level individually.

Vocabulary:

Vocabulary (or lexical comprehension) is the foundation reading skill, even before phonics. Lexical comprehension is simply recognizing that language is composed of different words with differing meanings. Many studies over the years have demonstrated a strong correlation between a child’s vocabulary and the quality of their reading. In short, exposing a child to a wide variety of vocabulary words will yield great rewards down the line as they move up the pyramid. To build strong reading comprehension, start early by actively working to expand a young child’s vocabulary.

Phonological Awareness:

Phonological awareness is the ability to recognize and manipulate sounds in spoken language. This subcategory involves understanding the relationship between sounds and letters, which helps children decode and read words. This is a precursor to phonics and involves things like rhyme recognition, understanding that words can be broken down into parts, and that those parts can be manipulated to create language.

Phonics:

Phonics is the ability to connect sounds with letters and letter combinations. It involves understanding the relationship between letters and their corresponding sounds, which helps children decode and read words. For many people, this is treated as the beginning of reading. The phonics stage is where the child actually begins sounding out words. It is the phase in which you sit with your child, helping them work through the mechanics of sounding out letters to show how they form words.

Fluency:

Fluency is the ability to read with accuracy, speed, and expression. It involves automatic word recognition and the ability to read with appropriate phrasing and intonation. This is essentially the level of “comfort” a child develops with the act of reading. A fluent reader reads “naturally,” and can move from word to word with ease. Building fluency is very important for reading comprehension. This is because it “frees” the mind to focus on higher-level aspects of reading, such as context cues, mood, and implicit messaging in the text.

A reader who is not fluent will be vastly less likely to develop good reading comprehension. For example, someone who wants to learn to do tricks on a bicycle must first master balance to the point that they can balance almost effortlessly, reflexively. It is only after (and because) balance is mastered that the bicyclist can move on to other things like letting go of the handlebars, wheelies, and jumping. Without mastering balance first, however, these other tasks become impossible, because so much available muscle and energy must be devoted to simply staying up on the bike. Similarly, a young reader must be able to read fluently before he or she can devote energy to the aspects of a text that communicate meaning.

Comprehension:

Comprehension is the ability to understand the meaning of a text. It involves understanding the main idea, making inferences, and drawing conclusions based on the information presented in the text. A reader with solid comprehension skills can summarize or paraphrase what they just read in their own words, predict what might happen next based on context cues, pick up on implicit messages that might not be explicitly spelled out in the text, and answer questions about the text.

Comprehension as the Capstone of Reading

Reading comprehension is not a stand-alone talent that some children simply “have,” and others do not. It is the capstone of a carefully constructed pyramid of prerequisite skills, each one supporting and enabling the next. When we see a child who can decode words smoothly yet still stares blankly when asked what the passage was about, the problem is rarely a lack of effort or intelligence. More often, it is a missing or shaky layer somewhere lower in the structure—whether that be limited vocabulary, weak phonological awareness, incomplete phonics mastery, or insufficient reading fluency.

The good news is that this pyramid can be built and strengthened at any level. The earlier we begin—pouring rich, varied language into a child’s world from infancy, playing with sounds and rhymes, patiently guiding them through letter-sound relationships, and then practicing until reading becomes automatic and expressive—the stronger and taller the entire structure becomes. But even if you didn’t start early, you did not “miss” your window. You can go back to any stage of the pyramid at any point and rebuild those shaky foundations.

If you are dealing with a child who struggles with reading comprehension, rather than asking “Why don’t you get it?”, think in terms of the pyramid: “Which layer needs more support right now?” With targeted, patient work at each level, the seemingly mysterious gap between “sounding good” and truly understanding begins to close.

For more articles on reading comprehension, see:

Lost in the Scroll: Homeschooling and Reading Comprehension

8 Tips: Homeschool Reading Comprehension

Five Strategies for Building Strong Reader Habits

What are your thoughts on this topic? Join other homeschooling parents and me in the Homeschool Connections Facebook Group or in the HSC Community to continue the conversation.