Imperialism Explained: Principles, History, and Catholic Insights

This is the seventh article in a series. To learn more, see: “The -Isms Encyclopedia: Historical and Philosophical Ideas Explained” by Mr. Phillip Campbell.

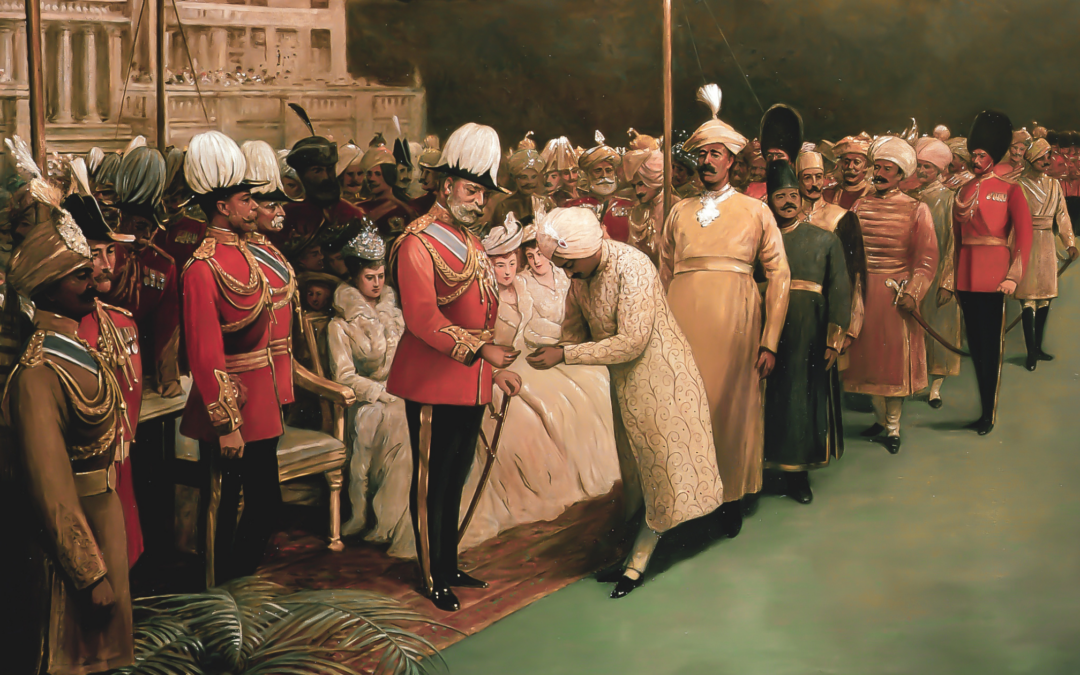

One cannot study modern history without coming across the concept of imperialism. While it no longer holds the prestige it once did, there was a time when imperialism was the dominant socio-political ideology of the Western world. Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, imperialism was the driving force behind European and American diplomacy. It resulted in much of the planet becoming subjugated to Western powers. The so-called Age of Imperialism lasted from around 1870 to 1914 and formed the immediate precursor to our current world order, which emerged out of the ashes of two world wars.

The imperialist era is typically considered to have begun in 1870 in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War with the creation of the German Empire as the major continental rival to the British Empire. And 1914, of course, marks the outbreak of the First World War, which would see the destruction of that German Empire and the toppling of Europe’s monarchies.

In this latest installment in our series on the isms of history, we shall explore the ins and outs of imperialism and how it came to define international relations for half a century.

Principles of Imperialism

All countries throughout human history have sought to expand their power & influence at the expense of their neighbors. From the Sumerian city states warring against one another to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, nations have always warred against one another in search of wealth, resources, and glory. But what makes 19th-20th century imperialism different from every other imperial adventure in human history?

The imperialism of the 19th to 20th centuries can be identified by several principles.

Colonialism

Imperialism was intimately bound up with colonialism, the idea that the good of the mother country required the acquisition of colonies abroad. The imperialist countries cited various reasons for this, including access to new markets to sell goods, strategic military purposes, control of trade routes, and access to raw materials. Nations also considered colonies a matter of prestige—for most countries, acquiring colonies was a sign of national greatness, an indicator that they were to be taken seriously on the world stage. While the United States favored Latin America, East Asia, and Polynesia for its colonies, the Europeans preferred Africa, Central Asia, and Southeast Asia. By 1900, Europe and the United States had colonized almost all of Africa and Asia.

For students of history who are familiar with the colonial empires of Spain, England, and France, one might ask how the colonization of the earlier Age of Exploration is distinct from 19th-century imperialism under discussion. Imperialism differed from earlier colonization primarily in its scope and focus. Earlier colonialism involved establishing settlements and trading posts. Imperialism, however, aimed for direct political and economic control over vast swaths of the globe. It was driven by industrialization and a desire for raw materials and new markets. This era also saw a surge in the number of colonial powers and an acceleration in territorial acquisitions. For this reason, 19th-20th century imperialism is sometimes called “new imperialism” to distinguish it from the colonial empires of the 15th-18th centuries.

Mercantilism

A distinguishing feature of imperialism was mercantilist economic policies. Mercantilism is a complex subject that could do with an article of its own, but for now it suffices to point out two aspects of mercantilism that were fundamental to imperialism.

First, the extraction of raw materials from the colony to support the industry or economy of the mother country. Imperialist nations typically treated their colonies as repositories of raw materials. These materials were extracted to benefit their own economies. Britain, for example, used India for its cotton, silk, spices, and rice. The Belgians extracted rubber, ivory, and minerals from the Congo. The Germans took diamonds, copper, and timber from their African colonies, while France took tin, rice, and rubber from French Indochina (Vietnam). The United States, meanwhile, extracted sugar and fruits from Hawaii, hemp from the Philippines, and coffee and tobacco from Puerto Rico.

The second component of mercantilism was protective trade policies and the attempts to create economic autonomy. Imperialist countries aimed to use their colonies to create insulated, self-sufficient economies. The goal was to create a fully integrated economy for the mother country that had no necessity to trade with any other power. The trade policies of imperialist countries were thus extremely competitive and outright hostile to one another. Other nations were viewed as competitors for scarce resources, not as potential trade partners.

Paternalism

Imperialist powers generally adopted a paternalist outlook about their conquests. Paternalism was the belief that colonial powers, like parents, had a duty to “civilize” and control colonized people, who were seen as incapable of self-rule. Essentially, the mother country adopted the role of a parent and viewed subjugated peoples as “children.” This helped the conquering power contextualize its actions as benign and moral. Sometimes this moral imperative had racist overtones. In the famous Rudyard Kipling poem, “White Man’s Burden,” written in 1899 upon the American conquest of the Philippines, Kipling speaks of the duty of the white man to civilize native Filipinos, which he characterized as “sullen peoples, half-devil and half-child.”

Nationalist Rivalries

We have already mentioned the economic hostility imperialist powers stoked against one another. This spilled over into the political realm as well, especially amongst the nations of Europe, where imperialist rivalries were made more acrimonious by centuries of hostility and competition for influence on the continent. These rivalries often shaped the course of imperial expansion. In Africa, for example, France tried to create an east-west axis across the country to stop Britain from joining its territories running north to south.

Russia and Britain attempted to outmaneuver one another in Central Asia. Germany likewise tried to block Britain’s expansion in Southern Africa by creating a band of colonies across modern-day Angola and Zambia. The French attempted to buffer Britain’s eastward expansion out of India in East Asia by securing the Siam Peninsula. At the same time, the United States used the explosion of the U.S.S. Maine in Havana Bay in 1898 as a pretext for depriving Spain of its colonial possessions and strengthening its military position in the Pacific and the Caribbean.

Who’s Who of Imperialism

As imperialism was not so much a fully fleshed-out philosophy as a bundle of political policies, there really is no founding father of imperialism comparable to, for example, Karl Marx’s stature within communism. We can, however, identify several important political and literary figures who functioned as spokesmen for imperialism, promoting the imperialist view of the world through their writings and policies.

Rudyard Kipling

We have already mentioned Rudyard Kipling (1865–1936), the British author who popularized the idea of the “White Man’s Burden” in his 1899 poem, arguing that Western powers had a duty to “civilize” colonized peoples. Kipling’s 1901 book Kim characterized Britain and Russia’s struggle for control of Central Asia as the “Great Game.” Kipling’s writings were instrumental in shaping the public perception of imperialism.

John Stuart Mill

We discussed John Stuart Mill in our article on Utilitarianism, but Mill was also an essential character in imperialist circles. John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) was a British philosopher who supported British colonialism in India, believing it could bring progress and good governance to “backward” societies. Following the paternalistic assumptions we described above, Mill equated progress with Europeanization, specifically, empowering Indians and other subject peoples through the imposition of British institutions.

Jules Ferry

Jules Ferry (1832–1893) was a French statesman and intellectual who defended French imperialism in the 1880s, arguing it was a moral duty and economic necessity to expand what he called France’s civilizing mission in Africa and Asia. Ferry would go on to serve as Prime Minister of France twice during the Third Republic, bringing his imperialist vision to France’s foreign policy. Ferry’s tenure saw France’s expansion into Indo-China and West Sudan and the establishment of a French protectorate over Tunisia.

Theodor Herzl

Another important figure to mention is Theodor Herzl (1860–1904). He was a Jewish journalist from Austria-Hungary who is considered the founding father of Zionism. This movement argued for the establishment and preservation of a Jewish homeland, particularly in Israel. Herzl’s writings supported colonial ideals, viewing European expansion as a model for future Jewish settlement in the Holy Land.

American Presidents

In the United States, presidents like William McKinley (1897-1901) and Teddy Roosevelt (1901-1909) exemplified America’s imperialist ambitions at the turn of the century. McKinley’s presidency saw the U.S. enter the Spanish-American War, which led to the acquisition of territories like Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. Roosevelt was known for his “big stick” diplomacy, emphasizing a strong military presence and forceful intervention in international affairs.

Imperialism in Practice

Sometimes, in this series, we discuss historical ideologies that have never been put into practice, such as utilitarianism or anarchism. Such is not the case with imperialism, which arguably was the dominant model of Western power for half a century, and even longer in many places. Therefore, we have a lot of data by which to measure how imperialism fared in practice.

Mother Countries

Whether imperialism “works” largely depends on who is asking the question. From the perspective of the mother countries, imperialism was undoubtedly an effective system. It consolidated power, expanded economic influence, and established military dominance. Imperialist nations gained access to vast resources, fueling industrial growth and wealth accumulation. Colonies also provided captive markets for manufactured goods and ensured a steady supply of commodities like rubber, cotton, and minerals. In other words, the colonies more or less successfully enabled the imperial powers to create the self-contained economies we discussed above.

Imperial powers also gained geopolitical leverage by controlling trade routes and strategic areas, as well as establishing naval bases. Britain’s control of Egypt gave it control over the vital Suez Canal, one of the most important trading hubs on the planet. Similarly, the United States’ control of Hawaii, Samoa, and the Philippines allowed it to establish naval bases throughout the Pacific, which served as a powerful check on the Japanese Empire’s expansion and would play a pivotal role in winning World War II.

Subjugated Nations

The story is quite different when considered from the perspective of the subjugated nations. For the conquered territories, imperialism was a different story. There indeed were some benefits received by the conquered territories. The ruling nations bettered the material infrastructure of the conquered territories by building railways, ports, and telegraph lines, as well as offered Western education models to local elites. However, these improvements were unevenly distributed. They generally benefited colonial authorities and local collaborators at the expense of the general population. And whatever roads and railways were built were a small consolation for the political disenfranchisement of the local populace, as well as the systematic stripping of natural resources that characterized imperial rule.

From a Catholic Perspective

The Church’s Complex Relationship with Imperialism

The Catholic Church’s stance on 19th-20th century imperialism was complex, generally shaped by its concern for the missions in colonial regions. While the Church never issued any document comprehensively dealing with imperialism, several statements were relevant to different aspects of the imperialist system.

During the heyday of imperialism, the Church did not reject imperialism in itself, focusing instead on addressing specific injustices that often occurred within the imperialist framework. For example, Leo XIII’s 1888 encyclical In Plurimis addressed the issue of slavery and other forms of compulsory labor still being used in certain colonies. While Leo does not call for an end to colonial occupation, he insists that the imperial powers respect the freedom, rights, and culture of indigenous peoples.

Missionary Efforts and Critiques of Nationalism

Pius X, Benedict XV, and Pius XI were all ardent supporters of the Church’s missionary work in colonial lands (which typically followed in the wake of imperial conquest). Still, they also critiqued the rabid nationalism and international rivalry that imperialism bred. These popes warned missionaries against conflating evangelism with Europeanization and condemned the imperial powers’ use of Catholic missions for political ends. These admonitions can be found in such documents as Ad Beatissimi Apostolorum (1914), Maximum Illud (1919), and Rerum Ecclesiae (1926).

The Church’s attitude towards imperialism can be best be summed up as pragmatic—while accommodating the political realities as it found them, the Church nevertheless critiqued certain aspects of the imperialist system it found contrary to the Gospel, injurious to the rights of the Church, or offensive to the rights of colonized peoples.

From Pragmatism to Advocacy for Human Dignity

Following the Second World War, the Church’s teaching placed an increasing emphasis on human dignity. It also emphasized the rights of peoples to guide their own national self-development. These teachings put the Church at odds with the inherently exploitative nature of imperialism. While not mentioning imperialism by name, the Second Vatican Council’s teachings on human dignity (as found in Gaudium et Spes and Dignitatis Humanae) nevertheless opposed the fundamental principles upon which imperialism was constructed. This was, to some degree, anachronistic, as by the time of Vatican II (1963-1965), the age of imperialism had long passed. Still, the Church’s teachings on human dignity and the self-determination of peoples would continue to hold relevance in the Church’s struggle against Communism and other totalitarian ideologies.

The Moral Incompatibility of Imperialism with the Gospel

However, even setting aside formal documents, it seems rather evident that imperialism does not square easily with the Gospel. The imperialist countries practiced economic and political exploitation under the guise of providing guidance, education, or progress. This mindset often ignores local cultures and indigenous needs, prioritizing the colonizers’ interests. Many historians believe that the persistent poverty of the Third World is a direct consequence of the exploitative nature of imperialist administration. While imperialism did confer some benefits on colonial territories—such as better infrastructure, administration, and the introduction of Christianity—the ends don’t justify the means. Most Catholics today would not see these as valid trade-offs for the political subjugation, economic exploitation, and cultural suppression that typified imperialist occupation.

In the Homeschool Connections Catalog

While Homeschool Connections does not currently offer a course dedicated exclusively to imperialism, it does come up in several. You can find discussions about European and American imperialism here:

Modern European History 1789-1991 with Phillip Campbell

Modern U.S. History 1865-2000 with Phillip Campbell

History and Culture of Imperial Russia with Carol Reynolds

Eleanor Nicholson will teach a two-part course on British literature past 1750 in Fall 2025 and Spring 2026. The course is eligible for college credit and will explore classic British literary works set against the historical backdrop of the British imperial era.

In Closing

Imperialism was a complex and often troubling force that profoundly shaped the modern world. Understanding its history helps us better appreciate the blessings of human dignity, self-determination, and true evangelization rooted in respect for all peoples. As Catholic homeschoolers, we are called to study these movements critically, through the lens of faith and reason, recognizing both the lessons of the past and the ongoing importance of promoting justice and authentic Christian witness in every age.

What are your thoughts or questions on this topic? To continue the discussion, join me and other homeschooling parents at our Homeschool Connections Community or our Facebook group!