Homeschooling: What Makes a Good Historical Movie?

What Homeschoolers Can Learn from Great Historical Movies: Tips for Teaching History Through Film

I haven’t had much luck with history movies lately. This year began with Napoleon, one of the worst historical films I’ve ever seen (which I savaged on my YouTube channel if you want the details). Now, the year is drawing to a close with Ridley Scott’s Gladiator II, another bungled mess that I found incredibly dull and frustrating.

These experiences have led me to reflect on what makes a good historical film—why are some beloved and others loathed? Does it matter how accurate or inaccurate they are? To what degree can liberties be taken with the history in the name of creative license? In today’s article, I will flesh out the ingredients that I find essential to a good historical movie.

NOTE: Not all movies mentioned are suitable for children. Parents are encouraged to preview films and use discretion before sharing them with their children.

1. Colorful Set Pieces

You might be surprised that I am starting with set design instead of historical accuracy, but I think this goes a long way toward making a historical movie enjoyable. History is very colorful. Whether we are talking about the brightly decorated temples of the Greco-Roman world, the multi-colored clothing worn by medieval people, or the rich and vibrant uniforms of the Napoleonic era, people have always loved color.

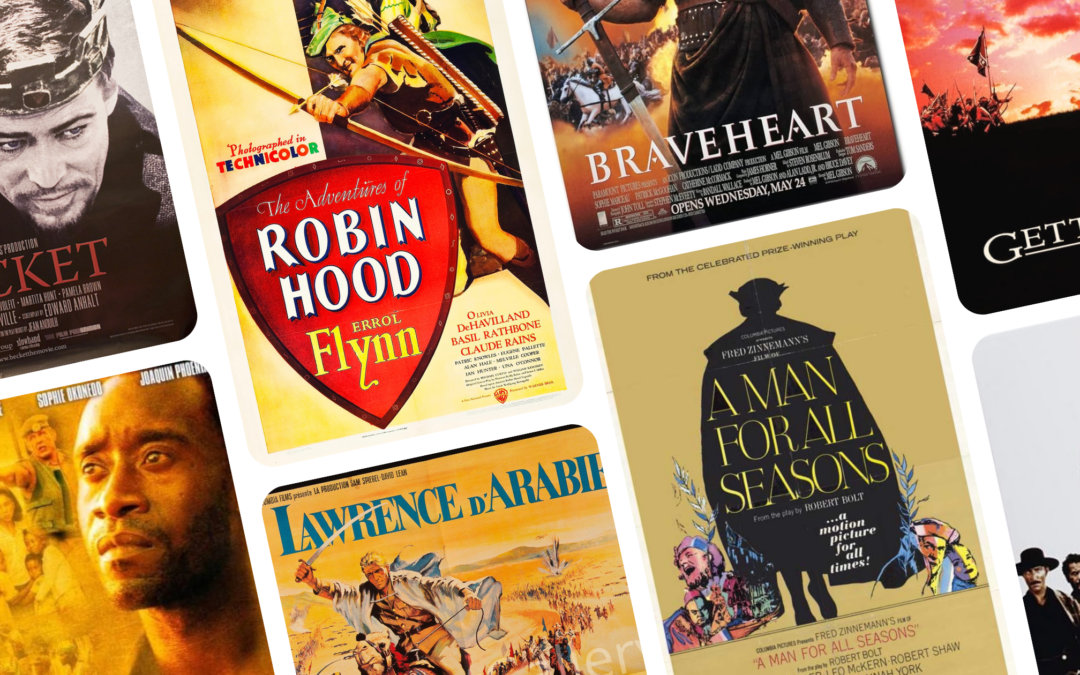

A good history movie embraces this vibrancy in its set and costume design. Besides being historically accurate, this makes the film aesthetically pleasing to watch. Think of the bright blues, whites, and browns of Lawrence of Arabia, the colorful ensemble of 1993’s Gettysburg, or even the 1938 Robin Hood with Errol Flynn. Or consider two Catholic favorites, 1964’s Becket with Richard Burton and A Man for All Seasons with Paul Scofield. These are all vibrant, colorful films, both in their costuming, set design, and natural locations they chose for setting. They are just nice to watch on a very fundamental level.

On the other hand, I have noticed that the history films I dislike have dull color palettes. The costumes are dull, earthen tones. The scenery is drab. Sometimes, they even put a dull sepia tone filter over the entire production, as in 2023’s Napoleon. I’m not sure what is behind this trend. Maybe they think historical people dressed this way? I suspect this is a deliberate attempt to make historical movies feel gritty, realistic, and grounded; if so, it fails. One can have grit and color (think of Braveheart or the original Gladiator). When historical movies are too drab, they are not fun to watch, regardless of their other merits. In contrast, consider the following images from Robin Hood (1938) and King Arthur: Legend of the Sword (2017). Which one do you think would be more pleasing to watch?

2. Historical Competence

Whereas most people speak of historical accuracy, I will speak of historical competence. I do not think a film needs to be historically accurate to be a good history film. You can have a great history film that takes liberties with the source material. But obviously, taking too many liberties can ruin a historical film by destroying your suspension of disbelief. What, then, is the magic spot for historical accuracy?

What I want to see in a history film is a demonstration that the filmmakers truly understand the historical period in which they are filming. They have studied the era and have a solid working knowledge of what life was like back then, as well as the ideas and attitudes prevalent in a given epoch. In other words, the movie must feel like it “belongs” to that era.

I understand that liberties must be taken with history to get it into the cinematic format. One must condense events that took years into much shorter periods, put rousing speeches that never happened into the mouths of our protagonists, and create personal and even romantic connections to give historical stories a more personal feel. Sometimes, liberties will be taken with a character’s motivations to make his or her actions more understandable. I’m okay with all this, so long as it is done to translate the story skillfully into the cinematic medium.

I am not okay with it when it demonstrates a complete lack of understanding of the time period. Or when it is gratuitous or due to laziness. Or when the changes are so substantial as to negate the value of the film as history. On this last point, a lot depends on what the film tries to be. One can take many more liberties in a period film with an entirely fictional plot and characters. Think of something like The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. If the film purports to portray actual people and events (especially if it is marketed as “based on a true story”), then I expect elevated levels of fidelity to the history. Think of something like Spielberg’s 2012 Lincoln.

Generally, there’s no hard and fast rule for how much deviation is too much. However, any deviations introduced should be creative decisions made in the service of the medium and in the context of an overall production that is accurate to the material and social conditions of the time.

If you’re curious about how accurately your favorite historical films portray the events and figures they depict, History vs. Hollywood is an excellent resource. This website dives into the fact vs. fiction of popular historical movies, providing detailed breakdowns of where filmmakers stayed true to history and where they took creative liberties.

3. Concise Plot

For a historical movie to be good, it still needs to be engaging as a movie. I would rather have a really entertaining film with historical errors than a historically accurate film that is not as interesting. At the end of the day, the film still needs to work as a movie. Much of this comes down to a clear, concise plot. Without a crisp plot, even the most historically accurate movie will fail.

A great example is the two Western movies Tombstone (1993) and Wyatt Earp (1994). These were back-to-back movies with the same subject matter but drastically different storytelling approaches. Tombstone (starring Kurt Russell and Val Kilmer) is a classic western that tells the tale of Wyatt Earp’s showdown at the O.K. Corral and the vendetta killings that rocked the town of Tombstone, Arizona, in 1881. The film took excessive liberties with the history, fabricating events and exaggerating the history for cinematic effect. It remains one of the most popular Westerns of all time.

By contrast, Wyatt Earp (starring Kevin Costner) aimed to tell the historically accurate story of the famous gunslinger. Consequently, the movie is much longer, its plot meanders, and critics complained about its rambling, unfocused storyline. Though it was much more accurate, it was less enjoyable as a film. It bombed at U.S. box offices and is remembered as a flop.

The takeaway is that a history movie still must function as a movie. One does not get a pass on story writing just because the history is accurate. A good movie takes the complex, often convoluted details of a historical event and finds a way to distill them down to their essential core. It remains faithful to history while presenting essentials in a dramatic fashion that draws the viewer in and keeps them engaged.

Tombstone (left) and Wyatt Earp (right) are two historical films about the same subject matter that received drastically different critical reviews due to the nature of their storytelling.

4. Clear Messaging

Finally, every film has a message. This isn’t just a Catholic hangup; it’s inherent in the nature of good storytelling. Throughout human history, the best stories present us with a lesson about human nature. They show us how vice leads to ruination, but virtue leads to a happy life. That’s not to say all stories have to have a positive message or a happy ending. The Greeks understood that these lessons could be displayed negatively, as it were, through tragedy—when we see characters ruined by their destructive choices, we are presented with counter-examples of how we should not respond to similar circumstances in our own lives. Incidentally, for an excellent Catholic take on these ideas, I highly recommend Stan Williams’ The Moral Premise: Harnessing Virtue and Vice for Box Office Success.

The best stories, therefore, have a clear message. There are a great variety of messages; it could be on the value of bravery in the face of overwhelming odds (Braveheart), loyalty to one’s convictions (Becket), or compassion amid horrific circumstances (Hotel Rwanda). We can even root for anti-heroes, like Clint Eastwood’s man with no name in The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly if we see him using his industriousness and wit to outsmart his more devious opponents, a movie whose lesson is that there is no honor among thieves.

So you can have a great deal of variability in the nature of the message… but there has to be some message. I have noticed a common trend among bad historical movies: you walk away uncertain of what the message was; you are unsure what it was “about.”

Walking away from Gladiator II, I had no sense of what I was supposed to take away from the film. It felt like a jaded, nihilistic production whose only message was that there are no ideals. Such a ridiculous approach to storytelling is not going to interest anybody. A good historical movie knows how to highlight the dramatic nature of history and tie that drama into the storytelling to exemplify a compelling message about the human experience.

What about you? What are some of your favorite historical films, and what makes a good historical movie? Join me and other homeschooling parents at our Homeschool Connections Community or our Facebook group to continue the discussion.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Mr. Campbell is working on a series of articles on using black & white film in our homeschools. You can find those articles here: Film Reviews for Homeschoolers.