In Pursuit of Wisdom: How Catholicism and Science Thrive Together

Strengthening the Bonds Between Faith and Science

I was recently blessed to publish a book titled In Pursuit of Wisdom: Catholicism and Science Through the Ages (Our Sunday Visitor, 2024). This comprehensive work explores the rich relationship between the Catholic faith and science over twenty centuries of history. It covers a wide range of topics, including ancient Christians’ theological and philosophical views on the material world and the role of monasticism in scientific development. Additionally, it covers key advancements in physics, chemistry, astronomy, and more. The book highlights the beautiful harmony that has existed between Christianity and science throughout the ages.

However, during my research for this book, I found that this harmony is not generally appreciated today, especially among the youth. Indeed, studies suggest that young people are leaving the Catholic Church in droves because of a perceived incompatibility between science and faith. Given that so much of this is based on tragic misconceptions, what can we do to turn the tide?

Unpacking the Myths: How Catholic History Supports Science

One thing that became abundantly clear from studying this long and fruitful reciprocity with science is that Catholic thinkers were never afraid of wading into the particulars, sorting out the nitty-gritty details with attentiveness and remarkable patience. In other words, if we are going to tell young people that there is no contradiction between science and religion, we need to commit to explaining how and why that is the case. But what does this look like?

Here, I’d like to present five ways we can strengthen the connective tissue between faith and science in our own lives and those of our children.

1. Take Our Religion Seriously

First, we must act as if we take our religion seriously. This might seem a no-brainer, but it’s an important starting point. If we do not want our children to act as if the Bible is just a collection of entertaining legends, let’s not treat it that way. If we want our children to take Catholic theology seriously, let us take Catholic theology seriously. If we believe the philosophy of nature is important, then let us open our children’s minds to wholesome philosophy.

Too often, we see Catholic parents—whose spiritual life is anemic, whose scriptural study is nominal, whose theological knowledge is non-existent—send their Catholic child off to a secular college and express dismay when their child abandons the faith. Let us first examine our own actions and convictions. “If we would judge ourselves, we would not be judged” (1 Cor. 11:30).

2. Scientific Literacy

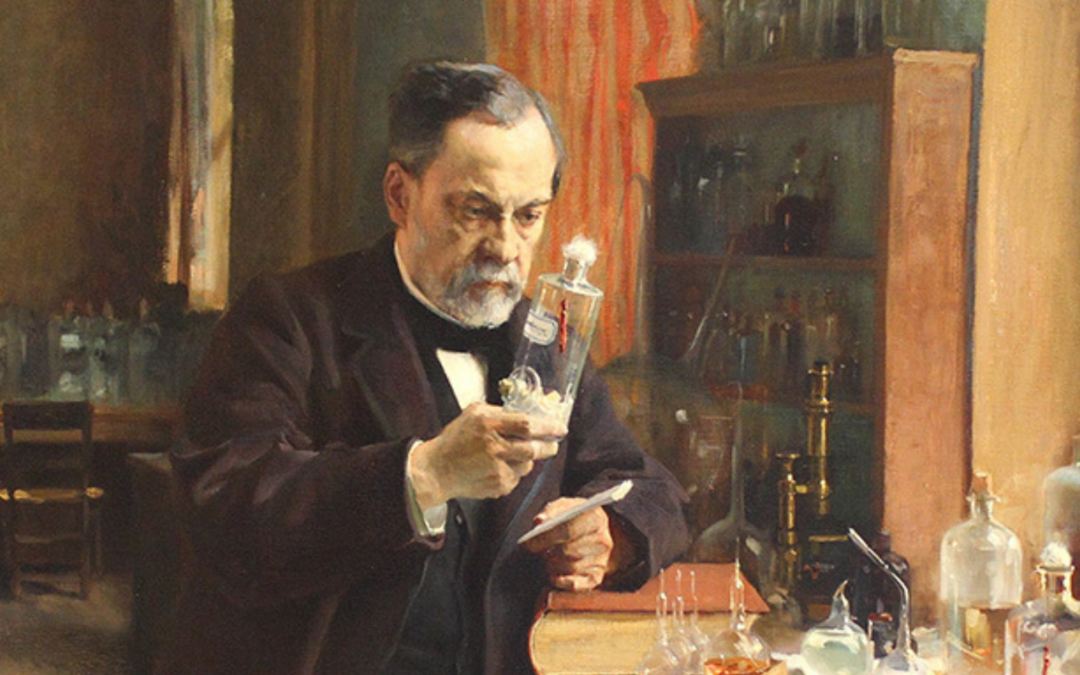

We should all do our best to be scientifically literate, especially as Catholics. For centuries, Catholic thinkers exhibited boundless curiosity about the natural world and the laws that govern it. The greatest theologians, such as St. Albert the Great or Nicholas Cusa, were consummate scientists. They viewed the natural order as a way of understanding God, like looking at His fingerprints left behind in the very structure of the created order.

If we, too, embrace the classical idea that “from the greatness and beauty of created things comes a corresponding perception of their creator” (Wis. 13:5), if we believe with St. Basil that “All the objects in the world are an invitation to faith, not unbelief,” then we ourselves should resolve to study the natural sciences with the same interest as our forefathers. (1) Most of us will never reach the intellectual heights of St. Albert, of course, but we should, at the minimum, cultivate a spirit of lively curiosity about the marvelous creation that surrounds us—to rekindle, in some respect, the ancient inquisitiveness that characterized Catholic intellectual life and pass this on to our children.

3. Tackle the Tough Questions

We should not fear traversing these expanses where faith and science overlap. When we paper over complex questions, it does not help anyone. Catholics sometimes want to address difficult questions by just repeating the mantra that “there can be no contradiction between faith and science.” However, merely repeating this truism will not help resolve anyone’s wavering faith. We need to be willing to wade into the particulars.

A personal anecdote will help illustrate my point: I recall not long ago being contacted by a friend of mine in the field of anesthesiology who was concerned about the moral implications of his career. What if he was required to administer anesthesia in the context of a procedure considered immoral according to Catholic ethics? Were there circumstances that rendered his participation in such cases more or less morally culpable? When should he outright refuse involvement?

It would have been easy to brush off his concerns and offer him platitudes in place of solutions. Instead, we spent considerable time wading through the moral implications of the particular situations he was concerned about, weighing the medical procedures against the norms of Catholic moral theology. When the discussion became sufficiently complex that I could no longer offer advice, I passed him off to a doctor of moral philosophy from the Catholic University of America.

Some months later, my friend followed up and said he had engaged in multiple fruitful discussions with the philosopher, who was happily able to settle his scruples. It was a process that took many months, but in the end, he obtained the answers he needed and had clarity on how the demands of his faith and medical profession intersected. This positive, faith-building outcome was only possible because everyone involved was willing to wade into the messy details.

4. Science vs. Scientism

It is also essential that we are keen enough to clearly distinguish between science and scientism, not allowing our secular humanist opponents to dictate the terms of the discussion by conflating the two. Scientism is the belief that all knowledge is reducible to scientific knowledge. Essentially, that science is all there is. As such, it is a form of materialism, a philosophical assumption that is not part of science but is often brought to the study of science by secularists.

Many Catholics who lose faith over perceived problems with science do so because they have embraced scientism as their default view of reality. This is generally not intentional but merely imbibed through engagement with the culture at large. It is ever more critical, therefore, that Catholics understand the difference between the two, between science itself and philosophies of nature that underly scientific assumptions. A grounding in the Aristotelian-Thomistic approach to nature provides a most salutary counterweight to the aggression of cultural scientism. It should, therefore, be incumbent upon every Catholic serious about these issues to obtain at least a basic appreciation for the natural philosophy of Aristotle and St. Thomas. (2)

5. Set the Historical Record Straight

Finally, we must do what we can to set the record straight about the Church’s relationship to science. Historically, the Church has nothing to apologize for and no reason for embarrassment in this regard. Indeed, for many centuries, the progress of science and the expansion of the Church were one and the same. Even in the midst of the alleged Dark Ages, the Church was the intellectual luminary of the Christian West.

Historian of science J.L. Heilbron, in assessing the scientific legacy of the Church, wrote: “The Roman Catholic Church gave more financial and social support to the study of astronomy for over six centuries, from the recovery of ancient learning during the late Middle Ages into the Enlightenment than any other, and probably all other, institutions.” (3)

This was expressed beautifully in a 1988 letter of Pope John Paul II to Fr. George Coyne, Director of the Vatican Observatory. Commenting on the reciprocity of faith and science, the pope said: “Science can purify religion from error and superstition; religion can purify science from idolatry and false absolutes. Each can draw the other into a wider world, a world in which both can flourish.” (4)

To Learn More…

If you’d like to learn more about this subject, first and foremost, get a copy of my book, In Pursuit of Wisdom. To go really deep into the topic, see this reading list: Fatih, Reason, and Science.

Finally, when it comes to a well-rounded science education for your children, Homeschool Connections has a variety of options for all ages. Catholic Homeschool Science Classes Online. Of particular interest are the History of Science courses.

What are your thoughts on this topic? Join me and other homeschooling parents at our Homeschool Connections Community or our Facebook group to continue the discussion!

(1) St. Basil the Great, On the Psalms, 32:3

(2) A good place for beginners is Peter Kreeft’s Summa of the Summa (Ignatius Press, 1990).

(3) J.L. Heilbron, The Sun in the Church: Cathedrals as Solar Observatories (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999), 3

(4) John Paul II, “Letter to George V. Coyne, Director of the Vatican Observatory, June 1, 1988.