Mercantilism Explained: Principles, History, and Catholic Insights

This is the ninth article in a series. To learn more, see: “The -Isms Encyclopedia: Historical and Philosophical Ideas Explained” by Mr. Phillip Campbell.

What is Mercantilism

When I was studying history as a young man, I frequently ran across the term mercantilism to describe the economic system of the early modern period. I confess I had never quite understood what this term meant. It was commonly used in textbooks to refer to things like the East Indian spice trade, the American fur trade, or the African slave trade, corresponding roughly to the period from the discovery of the New World up to the Industrial Revolution.

It clearly had something to do with international trade, merchants, and shipping. But what is so unique about that? Haven’t human societies been engaging in trade since the dawn of time? Indeed, some of the earliest written records are mercantile receipts from the ancient Sumerians. Mercantile activity is certainly nothing new or unique. So, why do we specifically call this early modern era “mercantilist”?

I will admit that mercantilism is an admittedly loose term. Similar to other terms like feudalism and fascism, it is easier to conjure up images of the mercantilist era than put a strict definition to it: vintage sailing vessels traversing vast oceans in search of resources, trade (often exploitative) with indigenous peoples in Asia and the Americas, hard-nosed European merchants who doubled as explorers and conquerers establishing European outposts in distant lands, and rich cargoes of spice, furs, rum, and all sorts of goods arriving at European ports. We recognize mercantilism when we see it, even if we can’t define it with precision.

Since my high school days, I have read extensively on the early modern period. While the term remains somewhat hazy, I think we can flesh out the principles of mercantilism a bit further to gain a better understanding of the system’s unique nature.

Principles of Mercantilism

First off, what is mercantilism exactly? Is it a political philosophy? Is it an economic system? Or perhaps it is a method of social organization? The answer is yes. Mercantilism is best understood as a European socio-economic arrangement that overflowed into every aspect of national life. Political ideology was grounded in mercantilist assumptions. European economies functioned on a mercantilist framework. And European society, especially at its upper echelons, was defined by the finished goods made available by the mercantilist trade networks. It was as much a part of the early modern zeitgeist as liberal democracy is to our own era.

So, what are the fundamental ideas of the mercantilist system? Some of the foundational principles of mercantilism include the following.

Trade Surpluses

Mercantilist kingdoms such as England, the Netherlands, and Spain aimed for massive trade surpluses. This means they wanted to export as much as possible while importing very little. The goal was to create national self-sufficiency by producing as many products within the realm as possible while exploiting other nations for profit. This was often enshrined in law.

In the 17th century, England worried that its citizens were buying Dutch textiles, enriching a rival nation. To stop this, Parliament passed the Navigation Act of 1651. This law forbade Englishmen from importing Dutch goods and required them to buy only from English merchants. In this way, England minimized imports while maximizing exports.

This view treated other countries as rivals to be competed with. In the view of the time, for English merchants to prosper, it had to be at the expense of Dutch merchants. The national economy was considered a highly competitive field of winners and losers. This view is generally known today as “protectionism” because it aims to protect the domestic economy from foreign competition.

Suppression of Competition Through Monopolies

Following from the first point, mercantilist economies sought to ensure these trade surpluses through state control over parts of the economy. They did not “run” or “manage” the economy in the socialist sense. Instead, mercantilist nations believed that private competition within certain essential sectors of the economy would be detrimental to the public good and therefore sought to stifle competition by granting monopolies.

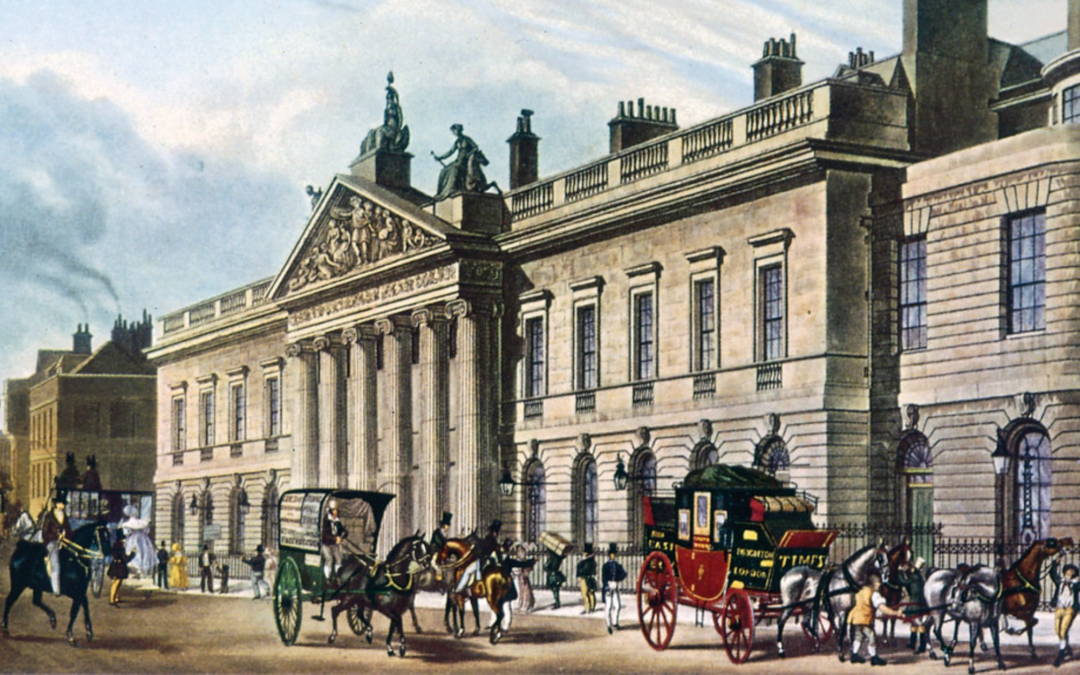

In the mercantilist context, a monopoly occurs when the government of a nation grants exclusive legal rights to a specific market or product to one particular company, excluding all others. For example, the British granted a monopoly to the British East India Company (1600–1858), while the Dutch did the same for the Dutch East India Company (1602–1799). This meant that the British East India Company was the only British company allowed to conduct business in the East Indies, and the same applied to the Dutch.

No other British or Dutch companies were allowed to compete with the monopolies in the East Indies. These monopolies were often granted sweeping powers, including the authority to establish colonies, build forts, administer territories, engage in warfare, and even carry out the death penalty. A monopoly sometimes functioned as a “state within a state” within the broader realms of the kingdom. For example, the British East India Company literally ruled India from 1757 to 1858, when the Crown took control of the colony.

Nations granted monopolies because they believed that competition would harm trade by driving prices down and hurting merchants, which would result in lower tax revenue for the government and smaller returns for the merchants. Competition was encouraged between rival countries, but discouraged among companies within the same country. Sometimes, monopolies could be sold to companies as a means of raising money for the crown, as often happened in pre-Revolutionary France. Occasionally, the government itself would hold the monopoly, as with the French Gabelle, a government-held monopoly over the mining and sale of salt.

It should be noted that not every aspect of the economy was monopolized, only those sectors considered vital to the nation’s economic good.

Colonies for Resource Extraction

Mercantilist nations wanted complete economic self-sufficiency. Their ideal was a closed system where everything needed could be produced within the nation’s control. Of course, no country has all the resources it requires. This made colonies essential. Under mercantilism, colonial expansion and resource extraction were inseparable. Mercantilism thus went hand in hand with colonialism.

For most of the early modern period, colonies were considered primarily as opportunities for resource extraction. Spain drew silver from the mines of Peru and gold from Mexico. The English cultivated tobacco in Virginia while extracting rum and molasses from the West Indies. The Portuguese extracted sugar from the jungles of Brazil, and the French used the vast North American interior as a supply of furs. At the same time, the Dutch traversed the Indian Ocean in search of spices from the Moluccas. These resources would be sent back to the mother country, where they would be turned into finished goods and sold in European markets.

Much of this labor for raw materials was performed by slaves purchased from African slave markets. This gave rise to what historians have called the Triangular Trade. Finished products from Europe were traded to Africa in exchange for slaves. The slaves were then taken to the New World to extract raw materials such as tobacco, sugar cane, etc. These raw materials were shipped back to Europe and turned into finished goods, some of which would be sold in Europe and others which would be traded in Africa by slave traders for more human chattel.

Under mercantilism, the colonies were essentially viewed as ATMs from which the mother country could extract wealth in the form of raw materials. It was only later that the kingdoms of western Europe realized the value of colonies in their own right as places to settle with surplus populations. The English were arguably the first to do this with the dense settlement of New England during the 1600s. Still, it was not until the following century, towards the close of the mercantilist era, that most nations began accelerated attempts to populate their colonies and construct infrastructure.

Who’s Who of Mercantilism

Mercantilism lacks a singular “father figure” comparable to Karl Marx in Communism. It was not a single ideology but a broad collection of economic, social, and political assumptions held in common by most political and economic leaders. Mercantilism did have its theorists and apologists, however (mainly among the English). Among whom the most notable were:

Thomas Mun

Thomas Mun (1571-1641) was a prominent English merchant and writer. He is considered to be a key architect of the surplus trade theory, advocating for a nation to export more than it imports to achieve a net inflow of wealth.

Josiah Child

Another English proponent of mercantilist ideas was Josiah Child (1630-1699), a notable merchant and politician who supported policies to increase national wealth through trade and served as governor of the East India Company.

Edward Misselden

Misselden (1608-1654) was an English merchant and adventurer who strongly advocated for the merchant class’s perspective on trade and protectionism. Misselden’s views were influential in shaping English parliamentary laws on trade during the 17th century.

Gerard de Malynes

The English mercantilist Gerard de Malynes (1585-1641) was a merchant who worked for the English royal mint and served as an English commissioner in the Spanish Netherlands. Malynes was chiefly concerned with questions of money supply. He claimed that the scarcity of currency in England during the 17th century was due to the speculation of the money changers. Such speculation would cause England’s currency to devalue, and for that reason, English goods were sold cheaply abroad, while foreign goods were sold expensively in the national market. He proposed various schemes for monopolizing the ability to mint coins throughout the realm, with limited success.

Jean-Baptiste Colbert

The French Finance Minister Colbert (1619–1683) was the best-known mercantilist theorist of the French and perhaps the most notable exponent of “pure” or classical mercantilism, promoting monopolistic economic policies to strengthen the French state and economy against rising commercial powers. Colbert served with distinction under King Louis XIV. His policies for strengthening France’s economy included increasing exports, decreasing imports, and building colonies. Colbert achieved this through protective tariffs, state-sponsored monopolies and manufacturing, and the development of a powerful navy to protect French trade on the seas.

Mercantilism in Practice

You will notice that the most notable apologists for mercantilism were English. This is not surprising, as mercantilism was most prevalent in seafaring countries, such as England and the Netherlands. However, all Western European countries partook of it to a greater or lesser extent.

Nations hoped the mercantilist system would profit from their colonial ventures, protect their maritime trade, and fill royal coffers. Historians debate whether the mercantilist system was effective. Some argue that the mercantilist system was a success because the colonial powers were enriched and empowered by their extraction of raw materials from the New World.

Colbert’s policies did strengthen France’s economy, and companies like the Dutch East India Company were wildly successful in their monopolistic enterprises. For example, the Dutch East India Company, at the peak of its influence, was worth approximately $10 trillion, adjusted for today’s inflation, making it the most valuable company in history. It is hard to argue that a $10 trillion company was unsuccessful.

Critics of Mercantilism

On the other hand, critics of mercantilism argue that even if mercantilism generated wealth, the system was not optimally effective. Towards the end of the mercantilist era, the Scottish economist Adam Smith (1723-1790) critiqued mercantilism in his famous book Wealth of Nations. Smith argued that mercantilism incorrectly assumed wealth to be in the accumulation of raw materials, whereas Smith believed that true wealth was in the productive work of the people.

Smith also believed that wealth comes from people freely making and selling goods, not from government restrictions or monopolies that mercantilists often supported. He believed that open markets, where people could trade freely without heavy government regulations, would make everyone richer by encouraging competition and innovation, even among different countries. Smith argued that all countries would be better served by allowing their people to trade with one another freely, thereby letting the laws of supply and demand determine prices.

Another critic of mercantilism was the French economist Frédéric Bastiat. Bastiat mocked mercantilist protectionist policies in his famous Candlemakers’ Petition, a satire suggesting that candlemakers should petition the government to block out the sun, a “foreign competitor” to the candlemakers since it provides people with free light. Bastiat argued that such restrictions harm consumers by raising prices and restricting choices.

Ultimately, critiques of mercantilism devolve into exercises in alternative history—trying to hypothesize about what would have happened had countries like England or France adopted different policies than they actually did. Such thought experiments, while interesting, are always speculative. While mercantilism was undoubtedly successful at transferring wealth to European countries and establishing lucrative trade networks, it is undeniable that some mercantilist policies hindered economic activity by hindering free trade and driving up prices through the granting of monopolies.

From a Catholic Perspective

The Catholic Church’s perspective on mercantilism inevitably centers on the morality of colonialism, which was an integral part of the mercantilist system. Here, we see the Church’s perspective has evolved with time.

During the Age of Discovery, the Church supported the colonial endeavors of Catholic nations as a means of evangelizing the peoples of the New World. The Church operated within a framework known as the “Doctrine of Discovery,” a theory that justified colonial expansion as a means to save souls. This idea can be found first in Nicholas V’s bull Dum Diversas (1452) and was subsequently repeated in future bulls throughout the era. Even so, the Church often condemned the violence and exploitation of natives that came with colonialism.

Some individuals, such as the Dominican Bartolomé de las Casas (1484-1566), vehemently protested the treatment of indigenous peoples under mercantilism. The Church condemned certain aspects of the system. This included slavery and the slave trade, which were condemned multiple times throughout the centuries. In other words, the Church did not object to mercantilism itself, only to its excesses.

As colonialism came to an end after World War II, the Church began reassessing its role in colonialism and took a decidedly more anti-colonial stance. In 1965, the Second Vatican Council’s document Gaudium et Spes emphasized the dignity of all peoples and criticized systems that exploit or marginalize others, implicitly challenging colonial legacies.

Pope Paul VI, in his 1967 encyclical Populorum Progressio, condemned economic and cultural domination that echoed colonial practices, calling for authentic development and respect for cultural identities. Pope Saint John Paul II and Pope Francis both made numerous apologies to indigenous peoples for injustices committed during the mercantilist era. In 2023, the Church formally repudiated the Doctrine of Discovery, saying, “The Catholic Church therefore repudiates those concepts that fail to recognize the inherent human rights of indigenous peoples, including what has become known as the legal and political ‘doctrine of discovery.”

The takeaway is that, while the Church once affirmed mercantilism in principle while condemning its colonialist excesses, the Church today seems to recognize that oppressive colonialism is so intimately wedded to mercantilism that it is practically impossible to have one without the other. The whole structure of mercantilism as it existed in the 17th century would thus be inadmissible from the Church’s perspective today. That being said, individual economic components of mercantilism—for example, the granting of monopolies or protectionist trade policies—are not inherently objectionable from a Catholic perspective. However, Catholics can (and do) indeed argue about their merits.

Continuing the Discussion

Mercantilism was never just about economics. It was a worldview that shaped politics, trade, and even morality. While it brought wealth and power to European nations, it also sowed the seeds of exploitation and conflict that have echoed through history. By studying mercantilism, we not only gain a better understanding of the past but also learn valuable lessons for today’s global economy.

In the Homeschool Connections catalog, the mercantilist era is discussed in the following courses:

Early Modern Europe 1648-1789 with Phillip Campbell

Economics as if People Matter with Phillip Campbell

American History Part One: Age of Exploration through the Civil War and Reconstruction with Chuck Chalberg

What are your thoughts on this topic? Join me and other homeschooling parents at our Homeschool Connections Community or our Facebook group to continue the discussion.