Where the Wild Things Are: A Case for Honest Storytelling in Children’s Books

Beyond Bedtime Stories: Challenging the Boundaries of Children’s Literature

Who Are Picture Books For?

It’s a simple question with an obvious answer. Picture books are for kids, right? But while children are the recipients of read-alouds and bedtime stories, picture books aren’t always written with kids first in mind.

Scottish writer and illustrator Debi Gliori points out that picture book creators need to be “…armed with a rough idea of what first publishers, then parents and finally, children might want (the order, sadly, is significant).”

Picture books must run through a gauntlet of gatekeepers before they are ever seen by a child, each with their own interests and ideas of what a picture book should be.

Can the art of storytelling withstand the army of agents, editors, executives, teachers, and parents who must each give a book their stamp of approval before it can ever hope to be read?

Sometimes, the answer is yes.

Where the Wild Things Are: A Picture Book Truly for Children

Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak is a picture book written for children—not publishers, not parents, and not teachers. And that’s awesome.

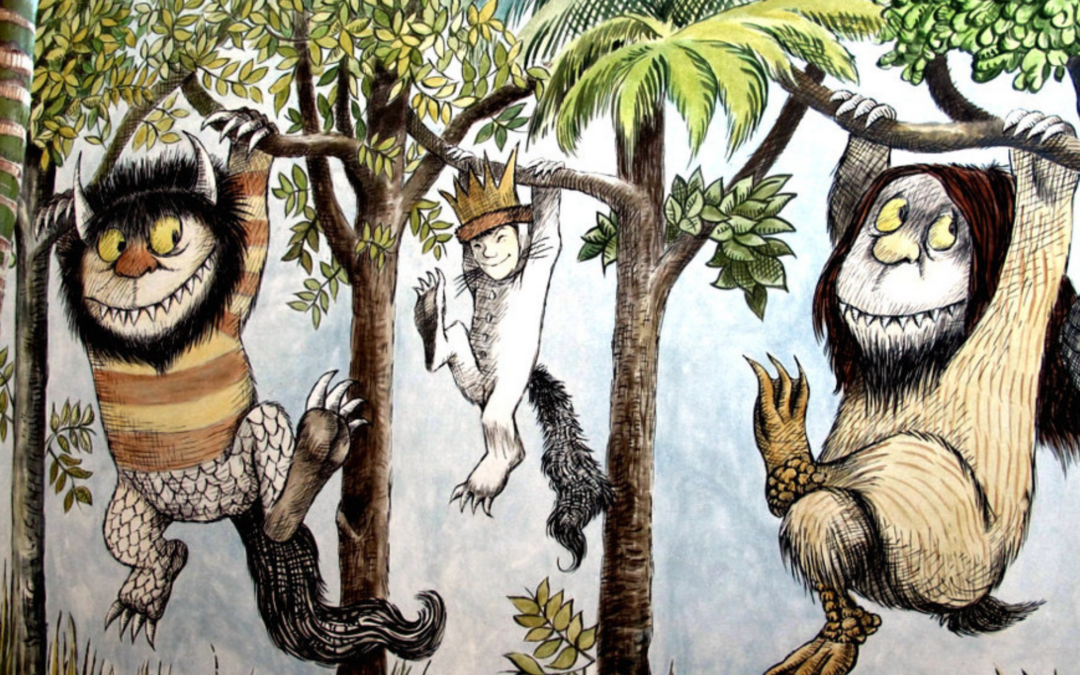

Where the Wild Things Are follows Max, a mischievous young boy who wreaks such havoc that he’s sent to bed without supper. When his bedroom transforms into a jungle, he sails to an island full of Wild Things. The Wild Things scrape their terrible claws and gnash their terrible teeth and roll their terrible eyes, but Max subdues them with the magic trick of staring into all their yellow eyes without blinking once, and he is crowned King of all the Wild Things.

Awarded the Caldecott medal in 1964, Where the Wild Things Are was recognized as the “most distinguished American picture book for children.” The book wasn’t without its critics, however. When Maurice Sendak’s masterpiece was criticized as being too frightening, he replied, “Where the Wild Things Are was not meant to please everybody–only children.”

The Battle Over “Hot” and “Warm”: When Publishers Control the Story

However, Sendak’s road to success wasn’t without its roadblocks. Sendak’s publisher expressed safety concerns about the word “hot” at the end of the book, when Max returns from his reign as king over the Wild Things to find his dinner “was still hot.” The publisher insisted that “hot” be changed to “warm,” but Sendak fought back: “It was going to burn the kid. I couldn’t believe it. But it turned into a real-world war, just that word.” Sendak eventually won by “just going at it,” he said. “Just trying to convey how dopey ‘warm’ sounded. Unemotional. Undramatic. Everything about that book is ‘hot.'”

Somehow, grown-ups have got this silly notion that, above all else, picture books must be safe. Any danger, no matter how small or imaginary, must be excised with surgical precision lest the fragile psyches of our children be shattered forever.

Call It the Disney Effect: Safe, Sterile Storytelling

Sendak was no fan of Disney, saying it was “terrible” for children.

“We are squeamish. We are Disneyfied. We don’t want children to suffer. But what do we do about the fact that they do? The trick is to turn that into art. Not scare children. That’s never our intention.

“I adored Mickey Mouse when I was a child. He was the emblem of happiness and funniness. When Mickey Mouse came on the screen, and there was his big head, my sister said she had to hold onto me. I went berserk. I stood on the chair screaming, “My hero! My hero!” He had a lot of guts when he was young. We’re both about the same age; we’re about a month apart. He was the little brother I always wanted. He had teeth. He was more dangerous. He did things to Minnie that were not nice. I think what happened, was that he became so popular—this is my own theory—they gave his cruelty and his toughness to Donald Duck. And they made Mickey a fat nothing. He’s too important for products. They want him to be placid and nice and adorable. He turned into a schmaltzer. I despised him after a point.”

Sanitizing Stories: The Problem with Protecting Children from Real-Life

Disney has a long tradition of rehabilitating dark and violent fairy tales into something considered appropriate for children. Some of these changes are necessary. I doubt the part in Snow White where the prince forces the evil Queen to wear red-hot iron slippers and dance until dead would translate well to the big screen. However, censoring supposedly unsafe or inappropriate scenes from Bluey, such as when Bluey plays ”penguin” by sliding around the wet bathroom floor or when Bingo asks her dad how babies get into mom’s bellies, seems more about assuaging squeamish executives and parents than about protecting children from harm.

Too often, children are deflected from anything adults find uncomfortable, neutering stories and rendering them lifeless, unrealistic, and boring.

According to Sendak, “The realities of childhood put to shame the half-true notions of some children’s books. These offer a gilded world unshadowed by the least suggestion of conflict or pain. A world manufactured by those who cannot or don’t care to remember the truth of their own childhood. Their expurgated vision has no relation to the way real children live. I suppose these books have some purpose: they don’t frighten adults.”

Why Safe Isn’t Always Better: The Power of Honest Storytelling

Disney is at its best in its most dangerous and desperate moments: Buzz Lightyear at his lowest point, about to be blown up by the sadistic Sid, or Simba coming to terms with Mufasa’s death and his own failure, only to be confronted with the new and seemingly insurmountable problem of a desolated Pride Land.

Mickey Mouse is best when he has teeth.

Children’s author Matt de la Peña asks, “Is the job of the writer for the very young to tell the truth or preserve innocence?” As if truth and innocence are incompatible when, in fact, it’s the comfortable lies that erode innocence and leave us jaded, as the Happily Ever After we were promised never arrives.

Matt de la Peña concludes, “Maybe instead of anxiously trying to protect our children from every little hurt and heartache, our job is to simply support them through such experiences.”

Two-time Newbery award-winning author Kate DiCamillo doesn’t ask whether we should tell the truth, but rather, how do we tell it? “For all of us trying to do this sacred task of telling stories for the young: How do we tell the truth and make that truth bearable?”

A Story for the Brave: Where the Wild Things Are

How do we make the truth bearable to our children? Even more perplexing, how do we make the truth bearable to the adults tasked to tell it?

Grown-ups sometimes fear telling children the truth lest it’s too “hot” and burns them. But children like Max want their meals hot. A bland and lukewarm diet, while perhaps nutritious, lacks spice. No kid wants that.

Where the Wild Things Are bucks the trend of safe storytelling. First published in 1963, and still regarded as one of the greatest picture books ever written, Maurice Sendak’s powerful fable of imagination, discovery, and overcoming our fears, allows children to break free of the strict boundaries of the world of adults and experience the Wild Rumpus.

This is a story about confronting the wildness and unpredictability of our world, taming your monsters, and coming back home to find your dinner still hot.

It’s a book that captures “this inescapable fact of childhood,” says author Maurice Sendak—”the awful vulnerability of children and their struggle to make themselves king of all wild things.”

Embracing the Wild: How Honest Storytelling Transcends Age

In the end, picture books aren’t just for kids—they’re for anyone willing to embrace the adventure of storytelling. While adults may try to shape what is supposedly appropriate for young readers, the best picture books, like Where the Wild Things Are, tap into the raw emotions, fears, and triumphs of childhood. They speak to truths that resonate not only with children but with the child within every adult. By daring to be honest, even a little “wild,” these books remind us that stories have the power to challenge, comfort, and ignite imaginations, regardless of age.

What are your thoughts on this topic? Join other homeschooling parents at our Homeschool Connections Community or our Facebook group to continue the discussion!